No products in the cart.

Fleeting solutions: Passenger freighters lack longevity

[Note: All figures and information in this feature were correct as of May 30.]

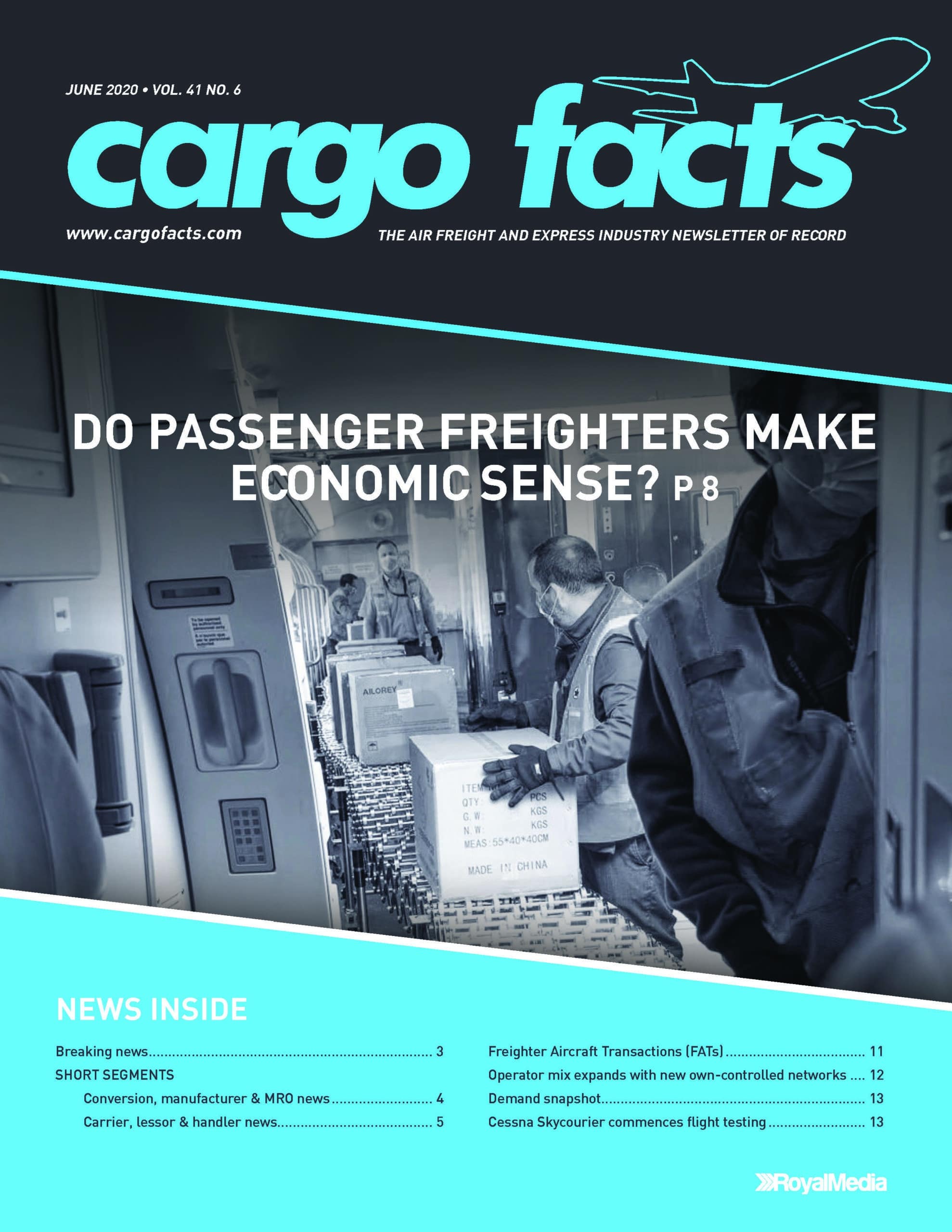

Just outside East Africa’s bustling Addis Ababa, Ethiopian Airlines has been toiling endlessly to modify a significant proportion of its passenger fleet to carry additional cargo.

Some twenty-two reconfigured aircraft, a wide mix of fleet types ranging in size from the Dash 8-Q400 to the 777-300ER, are now in cargo-only service with the airline, which already has a dedicated freighter fleet of twelve aircraft.

Though the most active player, Ethiopian isn’t alone. Around 120 aircraft across more than thirty carriers have now been reconfigured for cargo operations, based on Cargo Facts research. Including aircraft that haven’t been reconfigured, Cargo Facts has now recorded more than 1,600 passenger freighters that have been used at least once since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Increasingly, the capacity shortage has encouraged temporary reconfigurations and other solutions aimed at improving the efficiency of passenger freighters. Regardless of the degree to which a passenger freighter has been modified, the decision to transport only freight using aircraft originally designed to carry passengers might be a sensible and necessary response to the current capacity crunch. But as some parts of the world begin to ease restrictions and airlines tentatively plan a slow and partial resumption of their networks, we explore how much longer the practice of flying passenger freighters will last, and what sort of impact it could have on the market for full freighter conversions.

No one could have imagined the scale to which passenger aircraft would be used for the primary purpose of transporting cargo during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We note the distinction between “regular” and “reconfigured” passenger freighters. The former carry cargo in the belly only or in the belly, seats and storage compartments of the passenger cabin; the latter have had seats removed from the passenger cabin to create additional space for cargo.

Although the use of regular passenger freighters has steadily increased since late March, the trend of removing seats to increase the available cargo capacity appears to have gained momentum in May. This has been particularly evident in Europe, with Air Belgium, Air France, British Airways, Finnair, Hi Fly, Maleth-Aero, SmartLynx Airlines, and TAP Air Portugal joining Aegean Airlines, Austrian Airlines, Blue Air, Condor, Icelandair, Lufthansa and SkyUp Airlines operating reconfigured passenger freighters.

Elsewhere, China Eastern Airlines has already reconfigured ten A330-200s and is reportedly planning to modify four more.

Temporary reconfiguration does not require a process that mirrors full-freighter conversion, which is costly, involves extensive structural modifications, and normally takes an average of at least three months. Instead, reconfiguration is mostly a process of removing seats — usually only economy class due to their relatively simple design and construction — entertainment systems and wiring, installing fire extinguishers, and designating cargo-loading zones on the floor.

Avianor, the Montreal-based aircraft cabin and engineering specialist that was one of the first to develop a reconfiguration solution with Air Canada as launch customer, told Cargo Facts it only took about a week from the initial conversation with Air Canada to the redelivery of the first 777-300ER (41525). Most other temporary reconfigurations we’ve seen have also taken just a handful of days.

In terms of pricing, Avianor told Cargo Facts it varies, ranging from an engineering solution in which modification kits are delivered to the airline to be executed elsewhere, to a full MRO package that includes storage of the removed seats and modifying the aircraft back into passenger configuration. Excluding the initial consulting and preliminary engineering, for a baseline configuration, an airline is looking at about $35,000 in nonrecurring engineering costs, and between approximately $30,000 and $60,000 for the kits, depending on the number of cargo zones.

Apart from the reconfigurations themselves, other companies are also looking to gain a share of the passenger-freighter market with other solutions. Ancra International told Cargo Facts it had been working in the last couple of months to develop special products specifically designed to carry cargo in passenger cabins. The first option, for airlines that have kept their passenger cabins intact, consists of a net and mat that secure boxes in seats and are attached to the cabin floor. Where seats have been removed from the cabin, Ancra is offering specialized cuboid-shaped netting that is secured to the seat track to restrain cargo on the floor.

ULD specialist ACL Airshop has also turned to building net and strap systems as an alternative option for aircraft without cargo loading systems.

Meanwhile, HAECO Cabin Solutions has launched a range of stowage products that allow airlines to carry cargo in the passenger cabin, consisting of a palletized version where seats have been removed, a seat frame variant, and box-shaped storage devices that fit onto rows of seats or on the floor between seat rows.

AmSafe Bridport, which makes cargo nets, restraints and covers, told Cargo Facts that while it is handling enquiries on a case-by-case basis because there isn’t an off-the-shelf solution available, its priority in the past few months has been to support and guide its airline customers while ensuring safety and compliance are not compromised in the rush to come up with new ideas.

AmSafe Bridport noted that a key consideration is the viability of designing, qualifying, certifying and producing a solution in the anticipated time frame required, bearing in mind impact COVID-19’s impact on airlines as well as aspects of aerospace manufacturers’ business, such as staffing development programs; global supply chains for materials and prototypes; testing; and obtaining certification.

“Design, qualification, testing and certification of a solution require significant investment, focus and resources, and to do it right necessarily takes time,” said Andy Davies, engineering director of AmSafe Bridport. “The viability element is primarily one of longevity of need, which is yet to be determined.”

Although appropriate for today’s market, analysis by Cargo Facts finds that profitable passenger-freighter operations are dependent on a high-yield market and other conditions which could disappear as swiftly as passenger freighters emerged.

To continue reading this article, see Page 8 of our June issue here.

Subsequent sections include:

- Operating costs of passenger freighters

- Parked pax aircraft and feedstock

- Impact of COVID-19 on freighter fleets