Podcast: Experts weigh in on UPS 2976 crash

‘Cargo Facts Connect’ talks with former NTSB investigator, FAA DER about MD-11F grounding

Airlines lose control when they outsource heavy maintenance, and that could be the root cause of the fatal crash of UPS flight 2976, according to a former FAA airworthiness inspector and NTSB major accident investigator.

UPS’ CF6-powered, 1991-vintage MD-11F (48417) failed to maintain its climb and crashed after its left engine separated from the wing during takeoff from Louisville, Ky. (SDF).

MROs under microscope

The FAA and NTSB should look closely at the maintenance checks carriers have outsourced to third-party MROs, Stephen Carbone, president of private maintenance consultant firm Aircraft Maintenance Safety Professionals, says.

A former FAA airworthiness inspector and NTSB major accident investigator, Carbone says in this week’s episode of “Cargo Facts Connect” that he believes there is not enough oversight from the FAA or quality control from airlines that outsource aircraft maintenance.

“Since the early ’90s, the airlines have relied a lot more on repair station overhaul facilities to do their work,” Carbone says. “And the problem with that is the airline loses control of the maintenance.”

Tragic similarities

In addition, the November crash had tragic similarities to a 1979 crash of an American Airlines DC-10 at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport (ORD) that killed all 271 people.

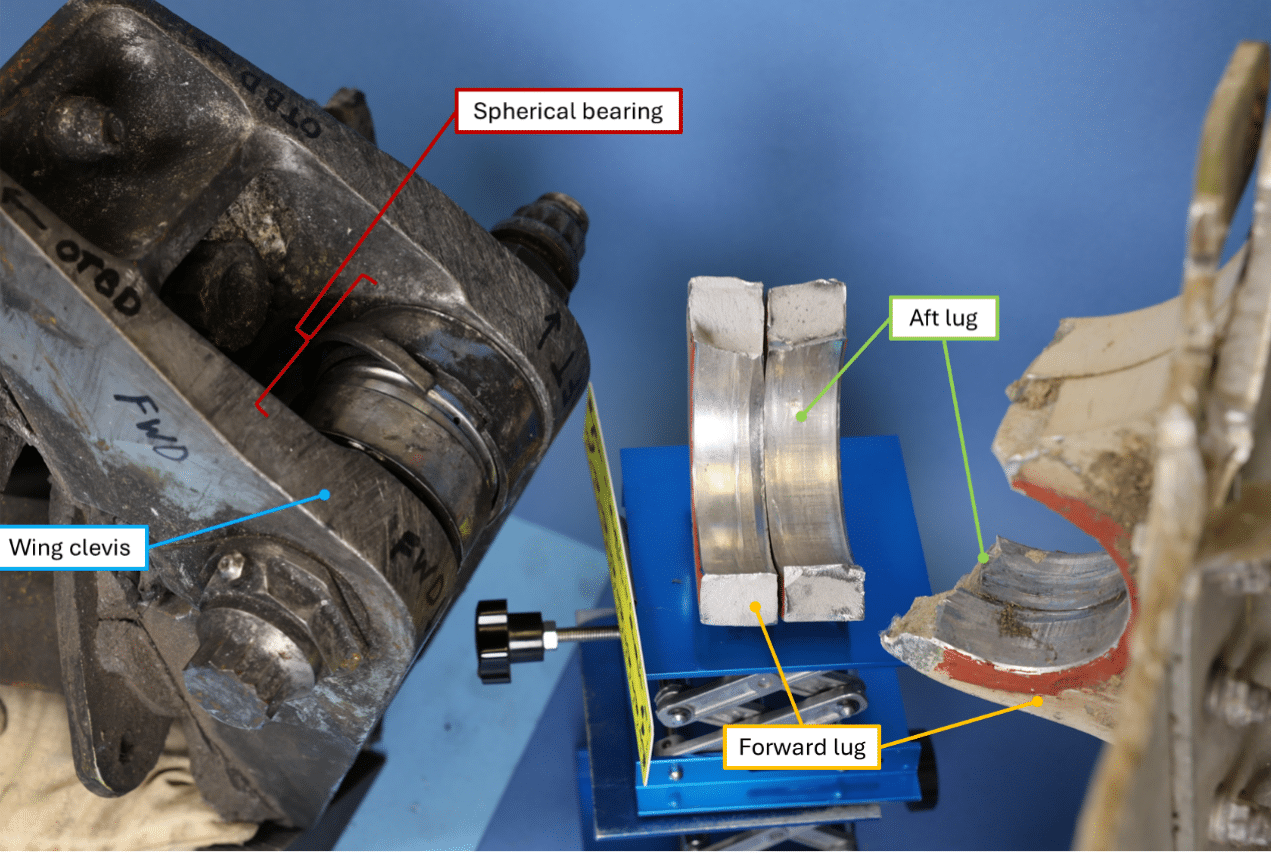

“The basic problem that caused the American Airlines DC-10 crash was the departure of the engine, almost exactly like the UPS MD-11F,” Steve Forness, managing director of aircraft engineering consultancy Air Flight Technical, says in the podcast. “It went up over the wing. The failure was the aft pylon.”

As a member of the McDonnell-Douglas team assigned to the American Airlines DC-10 crash and an FAA designated engineering representative, Forness aided the NTSB investigation, which identified improper installation of the engines as the cause of the aft bulkhead failure in the pylon.

Although the lessons learned from the DC-10 were implemented into the design and operation of MD-11s, the NTSB revealed in its Nov. 20 preliminary report of the UPS crash that it had discovered fatigue cracks in the pylon aft mount of the left engine.

As the NTSB investigation into UPS flight 2976 continues and around sixty MD-11Fs remain grounded, tune into this week’s episode of “Cargo Facts Connect” to hear Carbone and Forness share their insights with Senior Associate Editor Robert Luke on the accident and what could happen before the MD-11Fs return to service.

A transcript is available below. This transcript has been generated by software and some transcription errors may remain.

Robert Luke

Hello and welcome to this episode of cargo facts. Connect the podcast of cargo facts and the newsletter of record for of the aircraft, freighter and cargo industries for over 40 years. I’m your host, Robert Luke, Senior Associate Editor of cargo facts, and joining me for today’s discussion on the MD 11 F and the next steps while the aircraft remains grounded, are former FAA airworthiness inspector, NTSB, major accident investigator and president of aircraft maintenance safety professionals, Steven Carbone and FAA, designated engineering representative and president of Air flight technical. Stephen forness, welcome gentlemen, and I appreciate you joining me this afternoon for today’s discussion. If you wouldn’t mind, Steven, since you are the youngest. Steven forness, would you mind telling us a little bit about yourself and your background and how you came to be an FAA designated engineering rep and president of Air flight technical.

Steve Forness

Well, I started in 1977 working for McDonald Aircraft Company. Old Man Mac was still around. Worked on almost every military jet that McDonnell Douglas had worked on, many composite and metals programs did damage tolerance work in terms of writing computer programs to do damage tolerance. Spent many years going between different projects. My last job, I was deputy chief engineer on a $40 billion program for Boeing after we transitioned to Boeing. So that’s pretty much my you know that career. Additionally, while I was doing that, I also got my der in structures and damage tolerance from the FAA and worked that until probably about, I guess it was about 2020, I started it in 92 so I was on the side, Doing a lot of commercial repairs, modifications, even VIP aircraft at night and on weekends. So it was, you know, kind of busy, and that’s where air flight technical falls into place. We have auxiliary fuel tank systems for MD 80s. Put 2200 gallons of fuel on the cargo compartment. So I own the company, and have since day one, so worked, you know, many complex structural and engineering and engineering problems. So that’s just a you know, background spans a lot of a lot of engineering and mostly all aircraft. So let Stephen go.

Robert Luke

Yes, Stephen, please tell us a little bit about yourself. Mr. Carbone.

Stephen Carbone

okay, well, I began with Federal Express. It was called Federal Express back then, 1982 I’ve worked the MD 11, the DC 10, as a mechanic. That’s my background. Is maintenance. I went from there to in 2001 to the NTSB. I was the only amp certificated aircraft major, major accident investigator with any kind of airline experience. And I worked for there for three years. I did 10 accidents there, and then I went to, I went to the FAA, where I’ve done everything from regulation writing to overseeing, doing surveillance of major air, major air carriers, as I was telling Steve and Bruce before Robert before was that it’s anything East. I was responsible for most air carriers from anything east of the Mississippi and north of South North of South Carolina, meaning North Carolina up to Maine. So I was always involved with their auditing, their surveillance, surveillance. I’m also, since I left ISO 9001 lead auditor qualified, which means I can build programs of auditing for airlines or or whoever. And I’ve done certifications since then, of repair stations, part 135, operators, things like that, gotten their manuals set together so they can start operating. And I live in South Carolina,

Robert Luke

as do I we’re not too far apart from one another. Okay, good deal. Indeed. I’m right here in Columbia, but transitioning forward and thank you both for sharing that insight into your past and your work experience and defining your expertise in the subject matter we’re going to discuss. Steve forness, I want to start with you. You were part of the investigation team assigned to the American Airlines flight 191, DC, 10 crash in in Chicago in 1979 briefly, briefly explain the root cause behind the accident of flight 191, and the parallels you’re seeing with what happened to UPS flight 2976,

Steve Forness

let’s see the basics. Problem with the or basic issue that caused the crash was the departure of the engine, almost exactly like the MD 11. It went up over the wing. The failure was the aft pylon, close off bulkhead. The problem was that during maintenance, they would install the forward pylon fitting, which is a substantial fitting, and then drop the forklift, and that would slam the engine into the aft the engine aft fitting into the wing clevis. The problem was the wing clevis had a larger lug, or what more lengthy lug than the lug on the bulkhead, the close out bulkhead of the pylon, so that lug would impact a flange on the close out fitting, which actually was parallel to the ground, you know, close out panel on the pylon. And close out panel was attached to an integral fit, integral flange. That flange due to the fact that that upper fitting would hit the wing fitting would hit that flange before the wing pylon lug would actually impact the bottom of the wing closeout that would crack that flange. And then over time, with operational loads, the cracking would occur, and it would go down the backside, and later, the fittings would rupture. It wasn’t an immediate it had to have a substantial amount of operational use in order to get to a point where that failure occurred, the DC 10, having looked at the attached fitting that are in the NTSB report and other sources of information, they redesigned and removed that as a problem. The only thing I can ascertain from the stuff in the NTSB report is it is interesting that there is a crack, what I call crack striations, that would indicate that cracking had not only occurred, but had grown during time to operational loads In the in the lugs as described in the report. I don’t know if the failure of those lugs was a failure that occurred on the plane. It would take a lot more analysis. You’d need to know the operational loads, and I’m not making any assumption that those lugs were the failure point. The NTSB will do a great job of going over that and many times before they actually put out their final report. So the only unique thing that I can bring forward is the failure mechanism appears to be the same because in both cases, the engines rotated about the forward bulkhead before they actually left the aircraft wing. So in terms of the scenario, they both had the same or similar scenario.

Stephen Carbone

And it’s very the way that it’s designed to do it. We use come along to raise, to raise our engines when we’re changing the MD 11, DC 10 engines, or a 300 whatever wing engine. It was used come along to bring up the the engine into the pylon, which is different than raising the pylon into the space allotted for it. So as Steve pointed out, there’s there were pressures on there from the forklift driving it. What we have here, and I don’t think Steve and I are, neither one of us are speculating we’re just if we were king for a day, I would suggest to the NTSB to look in my, my, my suggestion would be to look in this direction. We’ve the airline since, since American 191, and actually since, since the early 90s, have relied a lot more on repair station overhaul facilities to do their work. Now, what the problem with that is, is that we, the airline, loses control of the maintenance because you have to, you have, in fact, if I, if I’m not mistaken, MD, elevens for both FedEx and UPS are done a heavy face checks are done overseas, which are pretty much out of the purview, the version, the visual purview of the FAA and the operator. So if UPS is located in Louisville, Kentucky, they can’t get over to, say, the Far East, to Japan or to Taiwan to do inspections as often as they really should, as opposed to being in the United States and having an overhaul facility. So a lot of your from an airline perspective, a lot of your wide body international airliners, don’t come back to the US to have maintenance done. They’re done outside the US, and that’s where I think the the focus should be is on if they have done adequate oversight of these repair stations that are doing engine repairs, also lubrications and visual and non destructive testing inspections, and If these people over there, if they’re if they’re not being properly overseen, to be doing maintenance per ups, or per FedEx or per united, then you start to see a lot of, I would think you would start to see a lot of problems as far as complying with the The airlines, what we call the camp, the continuous air worthiness maintenance programs. 10 elements to a camp is under sub part Lima, which is under parts 121, that camp is the entire maintenance program. And if there’s a breakdown in how that maintenance program is being done, out of out of the out of the awareness of the airline and the FAA, then that’s where I would see that a problem could arise where they’re not doing the due diligence to the engine pylons, and they are not doing the proper inspections, or they might not be doing the proper lubrications or anything else that needs to be done on those aircraft. And we’ve seen that happen in air Midwest, 5481 we’ve seen it happen in several airline accidents, or an incidents where the repair station has lost, the airline has lost control of the repair station.

Robert Luke

Okay, so Steven, just, I’m sorry to interrupt, just to piggyback off what you said, normally, from my understanding, and you can shed more like or insight on this. When a heavy maintenance check is done, whether it’s in the US or abroad, the carrier usually sends like, some type of quality inspection. Director or representative to oversee the maintenance work, to double check and make sure that all of the routines and the non routines have been fulfilled accurately and in accordance to FAA requirements. Are you saying that there’s not enough of there’s not enough presence from the carriers when these heavy maintenance checks are taking place, and that maybe they should consider taking these responsibilities back into their internal operations and doing it themselves.

Stephen Carbone

I would you said me, right? Yes, what I’m saying, right? This is going to sound a little bit like, like like, I’m, I’m trying to find a, what do they call that a when somebody’s making a problem out of thin air because of covid, the FAA backed off because they were not allowed to travel as much as well as the airlines were not allowed to travel as much so a lot of the things, and for instance, this air, this engine, may have been inspected the last time during that time period when nobody was overseeing these outside entities or even internal entities, when you start to lose control of the Maintenance Program. This is when you start to see these things happen. Because nobody is doing like, for instance, an ISO 9001 audit. Nobody’s going in there and making sure that the paperwork is done correctly, that the people are trained, qualified the air Midwest, 5481, accident I told you about. At the time, there were nine elements of the camp at the time, they violated eight of those and that was a repair station that was inside the United States. So when you start to lose control, and you start to lose oversight and doing your due diligence, if, if, for instance, UPS or FedEx has somebody overseas, they might have one or two company liaisons there. The FAA does not those are inside the United States, but they travel internationally to do their annual audits. Okay, so again, when you when you start to separate the the work that’s being done for maintenance outside the United States. And this is why I don’t think the the NTSB is looking in that direction, because they’re not aware of 145 repair stations, but FA certificated repair stations outside the US. So yes, I think UPS FedEx united, all of these airlines are going to have to step up their game and do more intense surveillance on what’s going on overseas.

Robert Luke

Okay, so is there a way that, based on what you’re saying, has the NTSB and the FAA and and other carriers involved under the Civil Aviation Agency kind of recognize that there’s a little uh, separation and understanding of each other’s respective roles and how to cooperate to, I would say, understand each other’s roles better so that these type of situations can be minimized. Like, what can we what can we do to bring more of a teamwork, collaboration and understanding of what NTSB does versus what the FAA does versus what the carriers are expected to do.

Stephen Carbone

Okay, I think something like this is a wake up call today that they need to boost what they’re doing outside. It’s been too long they’ve been sitting, you know, not, not doing their proper due diligence. It’s been too long. I think this some an accident like this is a wake up call for for instance, for right now, while the NTSB is doing this accident investigation, I don’t think the FAA and the ups and the FedEx and the United and Americans are sitting idle. I think they’re doing visual and non destructive testing inspections of all pylons, especially on the wing mounted engines on every aircraft. 5767, 8300, all of them, I think they’re taking this very seriously. While the ntsb prattles along on their investigation, they’re already doing something about it. So they’re anticipating what, what the, what the report is going to produce in two years. They’re already working towards that end, because the people that are involved in the FAA or in the certificate management office the CMO, they’re responsible for that airline, right? FedEx is in Memphis, UPS is in Louisville, their principal maintenance inspectors are already doing at it hardcore with the airline to get these, I believe, to get these things under control. Because this is, this is this is a, this is a real big wake up call to what happened.

Robert Luke

Okay? And Steve forness, I’m going to jump to you real quick as Steven, thank you for providing that insight on the maintenance perspective and. And kind of given us a rough idea of what the carriers are doing as the investigation is underway. Steve, what do you think Boeing is doing to not only assist with this process, but to ensure that there’s either airworthiness directives or service bulletins in place to safeguard these aircraft while they still remain in service.

Steve Forness

Well, right now you’ve got emergency ads on all DC 10 and MD elevens. They expanded it to so none of the DC 10 or MD elevens are flying passenger or freight. So what would Boeing do? Boeing is probably looking through all of their records and sizing up they have people, I’m sure, that are working with the NTSB embedded with them, helping provide everything from previous analysis to assessment, helping with the assessment of any NDT that takes place on the crashed airplane. Because what they want to do is they have to, they’re going to have to create a service bulletin as rapidly as possible to do inspections, and if there is any modifications needed to give those aircraft back to air worthiness standards. So embedded in the next ad is that come out or or maybe they’ll just modify the ad that they have. Boeing will issue a service bulletin with inspections and inspection follow on inspection times based usually on damage tolerance, crack growth analysis that they’ve performed, which is also based on, you know, the investigation and what they find in the aircraft. And my guess is they’re also working with at least the larger airlines, like UPS to go in, and similar to what Stephen said, at least on the DC template, they’re out there investigating. They’ve gone out, I’m sure, found the highest time to airplanes, okay? And they’ve also probably looked at the maintenance records through all of the other aircraft at UPS and said, Okay, Have we had any other incidents that may have contributed to this? So it’s it’s a big investigation, it’s a big analysis. It then will result in a very significant service bulletin that will come out as part of the update to the ad, or a separate ad, sometimes even multiple ad is come out associated with something like this as the investigation goes forward. That’s just normal, normal standard operating procedure for anything like this. And it’s actually a standard operating procedure for any ad. I mean, I’ve worked on many eight, what they call a box, alternative means of compliance to in to ad based on service bulletins. Just got done doing two very significant ones. Actually, the amox are in. They haven’t been approved yet. Where on the 730 sevens, they cut out the entire wing, or she’s fuselage splice joints, because they were an overlap. If you go back to the crash of the airplane in Hawaii, where the roof came off, we’re still working that problem as a 450 page SB that has to replace all of the major joints at the stringer, 410, and 14, those being from the top of the aircraft down on the top of the wing or windows and the bottom of the windows the entire length of the fuselage. They cut out the lower skin, and put in a different type of attachment of the upper and lower skins. So that just gives you an example of these things have gone on. I mean, this aircraft, these aircraft had, you know, 50, no, I think it’s 60,000 cycles to complete that repair. I mean, there have been many, many inspections that have taken place of that joint to ensure that they continue to have air worthiness before the repair is done. Where I got involved is, if there are existing repairs that that repair then interacts with, then we have to go in and make a new analysis of that area, with the existing repair combined with the repair and the SB, and that’s what the amocs that we sent in were. I’m just giving that as an example to give you an idea that these things don’t happen overnight. Sometimes the repairs are are designated to not have to happen for a sufficient number of cycles. So all of that is what Boeing’s trying to figure out. Boeing, Boeing, with the airlines, is trying to figure out, how do we get the airplane back in the air, air worthy, okay, which will be, I’m sure, a result of an SB, fairly significant SB, but SBS aren’t done overnight, so I know they’re probably burning the midnight oil up in Seattle trying to figure out how to, well, I take that back. The MDS are worked out of Douglas in Long Beach, Boeing, Doug, the old Douglas plant in Long Beach. So the people there are the ones that are probably doing all the work associated with should they put a team together just like we had on the Chicago crash? Okay, it took us. It took us three months, three and a half months of analysis before we even presented the results of that analysis, and we presented it at that time. That was the first damage tolerance, crack growth analysis on a commercial aircraft. We’d been doing it in the military for probably about 10 years, but that was the first that was done on a commercial aircraft, and we had to present our results to a team of experts. One part of the team was commercial professors from college. Another one, believe it or not, was headed by the Air Force who had the most experience in damage tolerance. Up to that point, we’ve been doing it on their F fifteens, like I said for years. So Chuck Tiffany and Jack Lincoln, Tiffany being the person who managed the civilian team and Jack Lincoln, who was the person who managed the Air Force team, both. You can google those two names, and you’ll they’re both the fathers of crack growth, along with Tom Swift for the FAA. So Tom Swift was on our team, those guys around those two teams, and the FAA was, you know, there to basically in at that point in time. They did not have any experts, so they were basically in a learning mode, listening to us make our presentation. That’s why Tom retired from Douglas almost immediately and became the National Resource Specialist for damage. And the FAA wrote new regulations. Okay? The 25 571, was a new regulation called, you know, basically for damage tolerance, requiring new and existing aircraft to meet certain requirements, which inspect or check for critical crack length. Aircraft can have cracks. We analyze them, and we determine that they do, you know, have cracks, but we put inspection intervals in to make sure that those cracks don’t go critical. Usually, the way it works is you get four inspections before you possibly think you would ever have a critical crack. So you basically work the statistics that four times the inspections and Stephen, I’m sure you’ll smile at that, because what, what I’m saying is that you expect the first inspection to find it, but you give them the opportunity to have four before it actually becomes a problem. So I’m trying to give you the ideas that this is a very intense effort that’s going on. It’s a very long effort that’s going to take place again. NTSB, will take two years before the report comes out, but that, SB, is not going to be two years, especially when you’ve got the number of aircraft grounded between ups, and I don’t know who else is flying them, but I’m

Robert Luke

Western global airlines. Western global

Steve Forness

Scott some, okay, yeah, the the Air Force had the KC 10s, but they retired those in 24 so the only place I know that the KC 10s are being flown, I think omega, which is an air refueling company that does, you know, works with the Navy to refute their air flight. Their aircraft off of California coast, they have a KC 10, so that’ll be grounded because they’re all based on the same mechanisms and same like I showed you, Robert in the little write up that I gave you, they don’t look that much different. The redesign took care of the problem that caused the crash in Chicago. Okay, that’s why I don’t want to speculate that that is anything to do with. This crash, okay, but it’s, you know, it’s a very expensive process that they’re going through. And like Steven said, there’ll be that. What will come out of that is heavy, heavy emphasis on maintenance inspections.

Robert Luke

Speaking of that, could we see a possible reduction in the number of cycles before the next special detailed inspection of the aft mount lugs as well as the wing clevis support for the engine pylons are examined in their next maintenance check?

Steve Forness

I mean, all that stuff will come out. It’ll all go but Steve was explaining the camp, okay, it’ll go into the maintenance records. The cards will all be updated. All the heavy inspection cards will be updated to have any new inspections that are required by the SPS, so, yeah, all that kind of stuff will get incorporated based on the SB into, you know, the manuals, all the card, what I say, the cards, the cards are camp program, the inspection cards.

Robert Luke

Now, as you mentioned that, of course, this investigation could be ongoing for the next couple of years, and we know that the nd 11 s will obviously begin to re enter service before then. What would be the ground or pathway for allowing that to happen outside of what we just discussed? How does the airline and Boeing and the FAA and the NTSB come to a solid understanding as to these are the corrective steps you have to take until we complete our investigation, but you have the green light to now go forward and start using this aircraft. It’s met the you know this, this aircraft that was first inspected has met the criteria. What would that look like from the from both of your perspectives?

Steve Forness

That’s real simple. It will be what’s in the SB when they issue the SB, that will be the agreement between the FAA and the SB will be incorporated into the ad language, so the FAA will approve the SB as part of the issuance of the ad so Boeing and the FAA have to agree that that SB is sufficient to allow air worthiness certificates to be given back to the aircraft once the SB is completed. I’ll let Steve talk about how that process goes once the SP hits the ground,

Stephen Carbone

just it’ll be incorporated into each phase check. You have phase checks, basically, just to elaborate a phase check, is dependent upon flight hours. So you might have what we used to call a b check was 500 flight hours, then you had a c check was, I think, 2500 I can’t remember the numbers off top my head. So they will intensify as Steve was talking about the task cards, those task cards will start to reflect the more involved and more involved inspections. For instance, they might go to an eddy current, which is a non destructive test thing. They might go to Visual, heavy visuals. I don’t know what, what, what the engineers are going to come up with, as far as suitable, but it’s going to be reflected in each of the phase checks as they go along, especially since this happened, it’s going to be if they don’t find out it’s something that is is found out to be like a repair station issue or overhaul facility issue or a maintenance provider issue. If it is something that was somehow designed implemented, it’s going to be reflected in those in those cards. By the way, the word, the word I was looking for before, was conspiracy theory. That’s, I don’t want to thought I was giving you a conspiracy theory, but that that’s where, when maintenance will see it, they’ll start to see the more involved cards and going on. And also you will start to see more of a presence of UPS, the FAA, ICAO, iyasa, all of these, these organizations that are hard pressed to make sure that the repair station overhaul facilities are doing what they’re supposed to be doing. You’re gonna be seeing a lot more audits, a lot more involvement of them overseeing and doing surveillance. That’s what I foresee

Robert Luke

and Steven, my question to you next is, if it is determined that this could have stemmed from contractual or outsourced maintenance work with an MRO facility, do you see these carriers starting to bring the maintenance work more in house to their own. Own day to day operations, because, as you indicated, these aircraft are now, you know, they’re acclimated to the old ABCD check system, whereas the current generation aircraft don’t follow that system anymore. They have their own way of counting that system into their modernized approach. And could this also because we’re talking about the older aircraft, which is no around 4040, plus years old. Could this accident lead to the the carriers like FedEx and UPS retiring the MD 11 freighter earlier than anticipated, because of now the additional expense and safety measures that have to be imposed in order to move forward with this aircraft type,

Stephen Carbone

I could foresee that there, in fact, I was having a conversation with somebody in the airlines the other day is they’re starting to, they think that the airlines are going to have to start buying new generation aircraft, because they do have a limited, a limited lifetime. For instance, the Aloha 231, accidents they talked about before with the convertible. It was because it not just because of the of the the the age of the aircraft, but because was constantly being pressurized, depressurized and put weakness into the metal, the corrosive environment of being over the ocean and all that, all added to that. So there’s a lot of factors that manufacturers engineering have to take into consideration to see the lifetime, if they can be expanded, that will will have, but I foresee you’re going to see a lot more retirements. And from what I understand, a lot of the airlines are looking back, looking into bringing the work back in. The problem is, is that they’ve sold a lot of it off. When Steve and I were talking about before the American net 587, accident, I was the the major accident investigator for maintenance, and then went to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where they did all their maintenance. I mean, they did everything there. A lot of that stuff has been contracted out and gone. So they’d have to rebuild that from from from scratch, almost in a lot of lot of shops would have to be rebuilt. But it’s, I think what, what we’ve seen ever and I know I go back to deregulation, all the these things happen is the more dependence to become more competitive. The airlines have become more reliant on contractors because of man power and equipment, hangar space, all of those things. It was less expensive to part out that or contract out that maintenance than to do it all in house. So all of that is going to have to phase back in again, but it’s never going to outside. Maintenance is never going to go away. It’s It’s too the the airlines are too involved internationally to make it cost effective to them to do all of their or most of their maintenance in house in for instance, Memphis or Atlanta or Chicago or whatever like that. You have limited space on the field. You have limited space and time. It’s going to be a major undertaking to do that 100% it’s going to be but they’re going to bring some of it back, but not all of it.

Steve Forness

Yeah, right now, the the mros in the United States are booked. I work with several of them. You know, if you have an airplane that’s coming up for a seat, check you better. You better start looking a year ahead of time to find a facility to do it. And I don’t mean just in the US, I mean overseas, you know.

Stephen Carbone

International.

Robert Luke

Thank you for sharing. Steve, now Steven, I want to ask you this, just because you’re the you know, one more experience on the maintenance aspect of the MD, 11 F and the aircraft we’re speaking of, do you think, and it’s just your opinion, only that these Mr. Rose, which are obviously been overworked over these last couple of years. You know, they’re booked through the roof passenger aircraft for not willing to you know, they can’t retire the older aircraft in their fleet because of the new order delays. We’re seeing material shortages. We’re seeing shortages and workforce that was created due to covid. Could that have possibly played a role, at whatever portion or percentage level into this accident taking place as well?

Stephen Carbone

Yeah, I just want to emphasize, I’m not saying it is the mros. I just think that they need to focus in that direction. I believe that’s very good possibility. I think that when when Steve was talking about what they did with the forklift. They didn’t do it to be malicious. They did it because they were trying to save time, and time is money in the airline business. They didn’t do it because they were trying to be lazy. They were doing it to save a cup, save a shave, a couple of hours off of an engine change to make the airline more efficient. So nothing is done out of maliciousness. It’s done because we lose focus of what’s going on. And when I was talking about with, for instance, the International overhaul facilities, it’s not that they’re doing anything to be malicious or lazy. They have 50 airplanes coming in, and they gotta get that Bay out, and they’re going to do what they have to do to get that, you know, meet the meeting, the the intent of the work task card, and get that plane out on time. So when you’re working against the clock, even when, even when I worked on the line maintenance control to go, okay, so how long is it going to take to fix that? I don’t know. I haven’t looked at it yet. Okay, so it’s everything is time. Everything’s pressure, as far as the airline version of it. But yes, I think that when we start to look at this, and I had the picture of the club of the mounts from the preliminary report up on the screen. I think this had a lot to do with improper inspections, or inspections that were not done correctly according to what was required. It’s not to say that that that is what it is, but like I said, if I was king for a day, that’s where I would look. Okay. Okay? Because you lose control when you are not doing there’s a certain sort of a pride when you do your own airplane. When you’re wearing that for instance, when I wore my FedEx shirt and I worked on a FedEx ramp, I always locked watch to make sure my FedEx plane took off. But when you’re doing 50 different customers, there’s not that attention to detail as much as you would be your aircraft my that’s my aircraft that has the same insignia that I get on my checks every week. So there’s a little bit of pride and culture that goes into proper maintenance,

Robert Luke

fair enough. And on that note, Steven Carbone and Steve forness, I want to thank you both for joining me on this discussion. You’ve not only given me some different ways of looking at what was has happened, but also what could happen going forward. I hope we get to work with you guys in the near future on a whole lot of different projects, hopefully not another accident. But just as we continue to move forward into 2026 I would look forward to relying upon your expertise for our up and coming events and features on engines and MRO repairs and how those things will progress going forward for the freighter industry. So thank you. Once again, I’m humbled by your time that you’ve taken to come spend with us and enlighten us as to not only the importance of aviation safety, but how the operation works behind the scenes.

Stephen Carbone

Thanks for having us.

Robert Luke

And that’s all the time we have today. For more coverage of the freighter aircraft and AAM market, visit cargofacts.com. Thank you very much for tuning in, and join us again next time.

Subscribe to Cargo Facts Connect on iTunes or Spotify, or download the episode on Transistor.

Cargo Facts LATAM 2026, the essential event for stakeholders in Latin America, will take place Feb. 10-12 at the Marquis Reforma in Mexico City. Learn more and register by Dec. 26 to take advantage of early-bird pricing.

Cargo Facts Asia 2026, the indispensable event for Asia-Pacific stakeholders, will take place March 23-25 at the W Shanghai. Learn more and register by Feb. 6 to take advantage of early-bird pricing.

The inaugural Cargo Facts Routes and Airport Conference will take place April 27-28 at the Marriott Al Forsan Abu Dhabi. Learn more and register by March 13 to take advantage of early-bird pricing.